The Inner Light

Picard bunks off work and plays at being an iron weaver for a few imaginary decades

The Enterprise encounters a probe in the middle of nowhere, and mock it mercilessly for how low tech it is. “Our tech’s better than your tech”, they chant. And yet, this apparently inadequate probe manages to beam a mental simulation directly into the mind of Captain Picard. Is it just me, or would that make a really effective weapon in the wrong hands...?

Words

Widely considered one of the greatest episodes of Trek ever made, this is another season five screenplay with a long and tortured history. It began during season four when Michael Piller had the idea for a story involving Picard experiencing another life. The writing team were on board for this concept, but when it came to cashing it out in a screenplay not one of them were able to make it work. As Joe Menosky later remarked: “Brannon Braga and I worked out at least a half dozen concepts ourselves – and they all failed.”

Then freelancer Morgan Gendel pitched an idea for a story about a probe beaming an interactive simulation directly into the crew’s minds. This was originally focussed upon an anti-war message, inspired in part by Gendel's Jewish upbringing and shaded by dark echoes of the Holocaust. Gendel recalled:

My thought was what if some civilization had been through some terrible war and didn’t want others to repeat it. Picard and Riker are hit with the probe and find themselves on a planet with storm troopers coming. They have to finish the story and get back to the Enterprise. It seemed entirely real to them while they were there and they had to escape these marching soldiers and a war which was leading up to a nuclear holocaust. Meanwhile, aboard the ship, they’re in comas.

The writers were intrigued by this premise, and Menosky and Braga suggested they marry this up with Piller’s old idea. Working with Ronald D. Moore, they provided feedback to Gendel and let him re-pitch several times. Amusingly, Piller had no idea how much his writers had worked behind the scenes to get Gendel’s pitch to succeed, and only found out about it years later!

However, Piller and Gendel argued about how to structure the episode. Gendel wanted the story to include much more of what was happening on the Enterprise, whereas Piller was more interested in his ‘alternative life’ storyline, and happy to side-line the rest of the cast. Clearly, Piller won out.

Finally, after Gendel had submitted a screenplay Piller was happy with, Peter Allan Fields was assigned to make revisions, as the end of the season was coming up fast and almost no screenplay survives contact with the production schedule unharmed. Menosky remembers that Piller himself contributed “substantial” rewrites of the dialogue, uncredited, determined to make this episode as good as it could be.

As for the curious title, this was Gendel’s contribution. It’s named after an obscure Beatles song:

‘The Inner Light’ was the B-side of ‘Lady Madonna’. I thought it would be fun to give every Star Trek episode I wrote a title that’s from a different, obscure Beatles song. I wanted to call “Starship Mine” ‘Revolution’, but they had already used “Evolution”. It was a little joke between me and me.

This was Gendel’s first successful sale to Star Trek, and it came to be considered one of the greatest these franchises ever produced. Piller named this (along with “The Measure of a Man” and “The Offspring”) as one of his three favourite TNG episodes.

I do have a grumble: the screenplay reproduces the trite and inaccurate idea that good scientists proceed from hypothesis to testing its validity. Essentially no breakthroughs in the sciences proceeded in this fashion, which means it serves no significant role in research processes whatsoever. It’s just a post-hoc justification for why the sciences appear so successful, itself something of a halo effect brought about by counting the successes and conveniently forgetting the numerous embarrassing failures, not to mention ignoring the negative impact of technological developments downstream from research. It’s not that knowledge hasn’t been refined over the centuries, its that calling this success ‘science’ doesn’t provide any helpful guidance to those seeking to refine knowledge! As with all things, the reality differs from the mythology. Still, this is sheer nitpickery on my part, and in no way detracts from the genius of this episode.

Acting Roles

To say that this entire episode is a vehicle for Patrick Stewart’s acting is an understatement. Stewart considered it the greatest challenge he faced as an actor in all seven years of filming Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Peter Allan Fields was greatly impressed with Stewart’s performance as Kamin, but even more impressed with guest performer Margot Rose, who plays his wife Eline:

She was absolutely superb, no ifs, ands or buts! I was grateful to have written something that an actress of that calibre had brought to life. She was excellent. I had never seen her before. I saw dailies, so I saw aspects of her performance that, unfortunately, the audience never got to see because the show ran long. They had to take out seven minutes.

Rose’s career has been mostly bit parts, and this was one of her few chances to play a leading role, which given how well she did makes you wonder why things never really took of for her. However, they did get her back for DS9, and she was in L.A. Law a few years after this appearance on TNG.

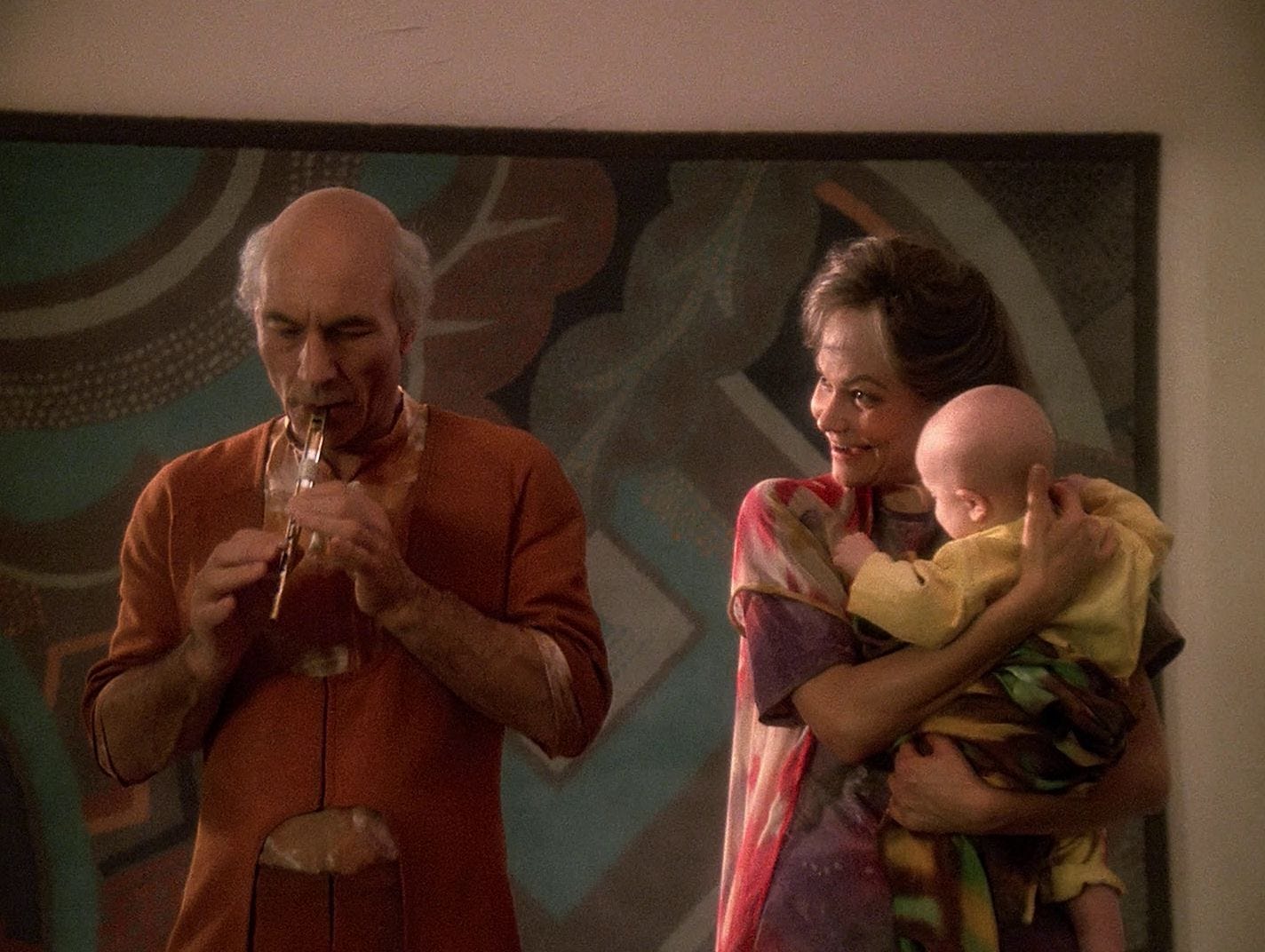

Incidentally, Kamin’s son, Batai, is played by Patrick Stewart’s own son, Daniel Stewart - here’s a picture of them both behind the scenes!

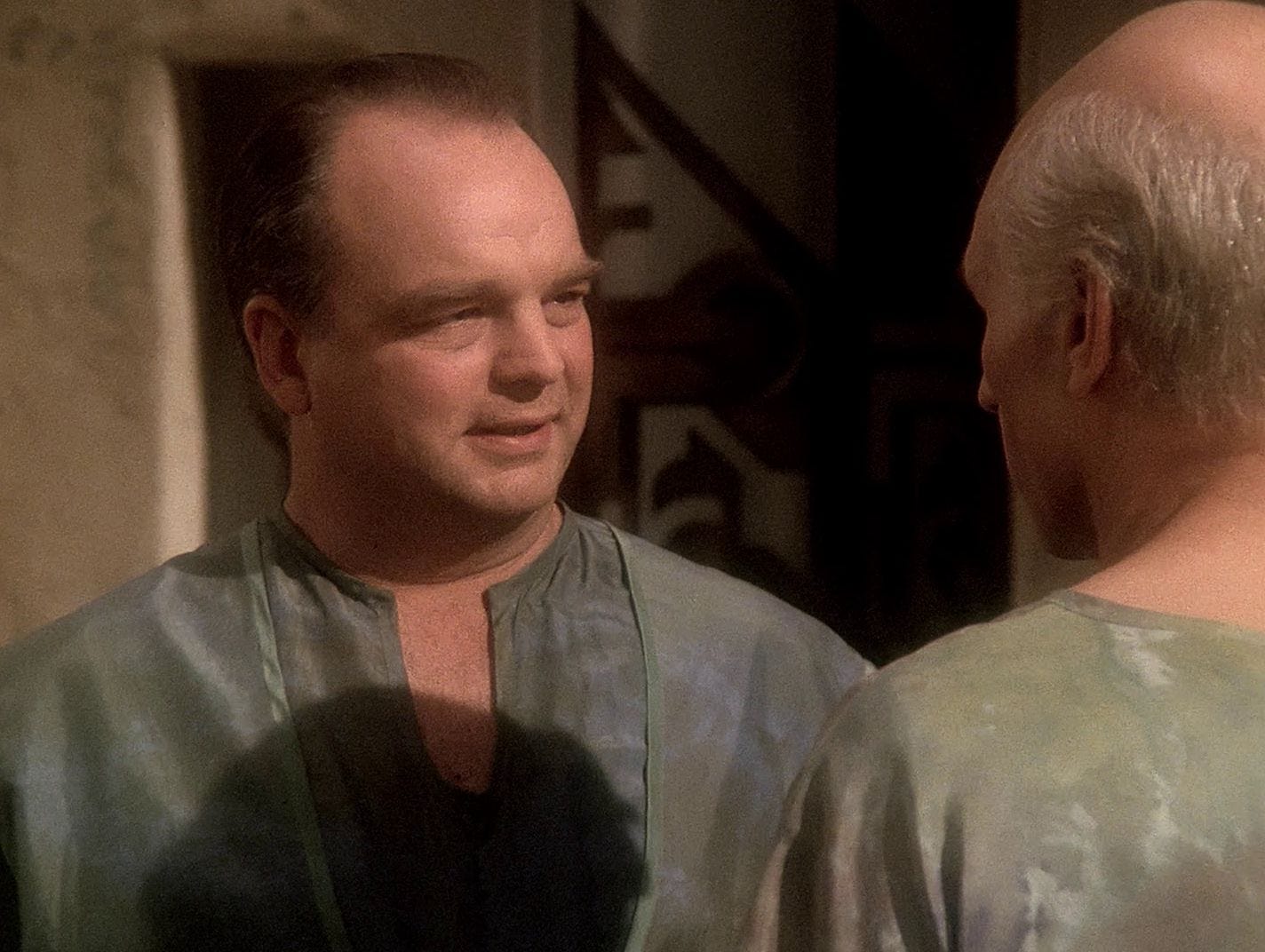

The character the son is named after, Batai, is played by Richard Riehle, who is fine here, although the role is not so central to the story as Rose’s.

You might recognise him as Tom Smykowski in Office Space, or from roles in Casino, The Man from Earth, or, erm, Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo. He had a recurring role as Walt Finnerty in Grounded for Life (43 episodes), and two roles in three episode of L.A. Law (before this role in TNG). And if you don’t recognise him in any of those, he has more than four hundred other roles, including appearing in Trek again in both Voyager and Enterprise. It’s quite the career!

But of course, everyone (except perhaps Rose) is overshadowed by Stewart, who was very moved by the shooting of this episode. He later remembered:

The most affecting sequence was the one scene where I was with the actress who was playing my wife, late one warm evening, sitting on a bench outside. I remember looking at her and thinking, “This is what it feels like to be elderly: sitting on a bench with someone you know so well, and this is what lies ahead.” That was the one time I had a sense of, God willing, what was waiting for me.

Every good soul is moved by this episode... but not my family, who didn’t like it. I am, frankly, stunned. I guess there were not enough explosions.

Models, Make-up, and Mattes

Most of the episode takes place in Sound Stage 16, which depending on your viewpoint is either taking a break from being ‘Planet Hell’, or being a particularly slow paced kind of hell-planet, where you get killed by drought.

The Kataan probe in this episode is a new studio miniature and if it’s modest, it’s still striking and memorable.

Memorable enough that we recognise it when we see the pendant with the same design!

But of course, this is an episode strong on story and light on special effects. That said, there is a matte painting, overlaid on a shot of Bronson Canyon, where a small amount of location photography took place (largely just for this scene).

The original (left) was painted by visual effects supervisor Dan Curry, although if you watch the remastered versions you’ll be seeing a digital reconstruction by Max Gabl (right). It’s extremely true to the original, though, and if I dislike this kind of revisionism in special effects, I do at least appreciate the skill involved in making it happen.

This episode was the first since Harlan Ellison’s 1968 “City on the Edge of Forever” (above) to win a Hugo Award, something very few TV shows can claim. It stands out as one of the great episodes in season five, and as one of Patrick Stewart’s greatest TNG performances - although it is topped, in my view, by an extraordinary episode next season. For now, however, season five goes into its cliffhanger episode on a memorable high.

I was there, and your recounting of the genesis of this episode is not accurate. It's like playing the old game "telephone," where you pass a whispered phrase down a line of people and hear how differently it comes out the end. There was definitely beneficial collaboration, but not as described. I'd be happy to set the record straight, although there are plenty of interviews dating back to closer to the episode's origin that would do so for you. - Morgan Gendel